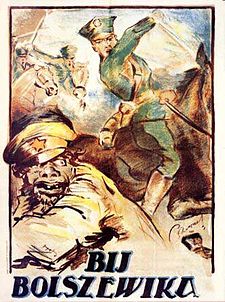

Well, the Polish Bolshevik war is over. We know, being armchair historians that peace reigns supreme in Poland for almost twenty years. The Miracle of the Vistula; the victory at the gates of Warsaw in August 1920, prevented the spread of Communism into Western Europe for a generation… and my, how Poland recognised that fact!

Polish crest of the 2nd Republic

In time, this victory and self-aggrandised political positioning, would become the main problem for Polish military and political doctrine and would eventually bleed through into their foreign policy, as well as ultimately leading to the destruction of the Polish 2nd Republic and as a reprisal, the NKVD’s murder of over 5000 Polish officers at Katyn. This is the reason why serving troops such as my girlfriend’s grandfather (see previous blog about the Podhale Rifles) had to hide all of their medals that proved they served in this period.

The excavation of the murdered Polish officers at Katyn, 1943

Senior Polish officers and politicians, most especially, Marshal Pilsudski himself, would make stubborn, foolhardy and sometimes bloody minded decisions which doomed Poland to dictatorship, illegal rule and a division from their closest allies, ultimately resulting in the loss of statehood between 1926 and 1989.

Zaloga makes some very informed observations on the state of the Polish military throughout the interbellum. The armies of the Russo Polish war were both heavily reliant on cavalry. This resulted in a cavalry bias not being particularly in evidence and because of the fact both sides were heavily reliant on cavalry, it was the cavalry that were instrumental in a lot of the victories. Because of this fact, the cavalry was widely lauded and somewhat revered in Poland, with the inevitable knock on effect that the cavalry officers became heavily entrenched, demonstrating a marked resistance to change.

Change did come however when in 1934, the lance was retired as a front line weapon, although training with it did continue. It is perhaps of some interest, if the comparison with the German army is made, that the lance was only retired from German cavalry regiments in 1927 and that too was amidst furious objections. Showalter also makes the observation that in the 1920’s the internal combustion engine was still a markedly primitive design, with early vehicles essentially being road bound. This led to the inevitable conclusion that in the underdeveloped Eastern European battlefields the cavalry still had an important place. According to Polish military doctrine it took three years to turn a man on a horse into a useful military asset.

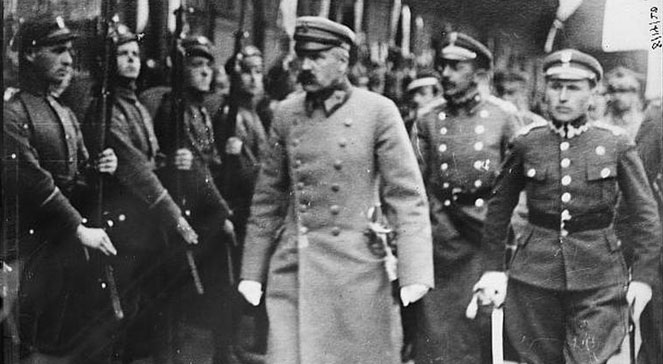

Pilsudski inspecting his troops

Looking at the Polish army as a whole, it can be said that it was Pilsudski’s pride and joy! What’s more, the Polish nation made the direct connection between their troops and their subsequent independence and would therefore spare no expense in its upkeep, allocating a larger percentage national budget than any other European country. The problem here of course, is that Poland was and still is a relatively poor country. Their massive percentage arms expenditure was still dwarfed by the industrial powerhouses of Germany and the Soviet Union during the ’30’s following Hitlers assumption of the Chancellorship and Stalin’s five year plans.

The ‘lens’ through which the Polish army of the Interbellum needs to be studied is of course, Pilsudski himself. He was not a professional soldier. He was an agitator and a politician with an assumed military position; and it showed. The Polish army demonstrated both his weaknesses and his strengths.

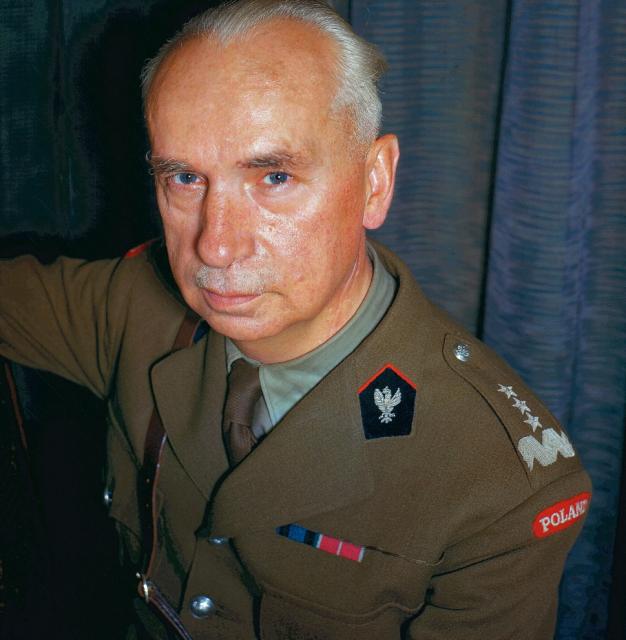

Polish Staff Officers

Higher Staff command skills and training was at best primitive and instituted an excessive reliance on ‘improvisation’. This may have been worthy of concern during wartime, although perhaps understandable BUT as a fundamental training measure during peacetime, it would prove to be catastrophic. As Zaloga points out, the majority of the Polish high command of the interbellum had not fought on the Western Front during World War 1 and were therefore, uninformed on the need for mechanisation and resistant to the idea of introducing new technology in tanks, automobiles and planes. This meant that by the time war broke out in 1939, the Polish army was still organised along the same lines as the respective armies of 1914 that included the Poles within their ranks. 30 Infantry Divisions, 11 Cavalry Divisions (representing 10% of the Polish army) with very little motorisation and primitive signalling infrastructure whilst the majority of the artillery remained horse drawn, which was in line with alliances made with France.

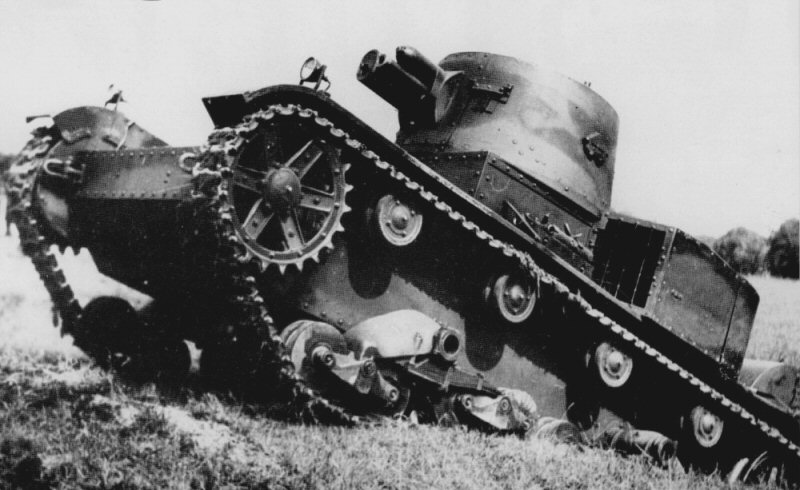

Recognition of the fact that Germany was re-arming was given during the ’30’s however, as in 1936 a commission was formed recommending that the Polish army should begin to modernise as a matter of urgency. A target was set for the implementation of 4 mechanised Cavalry Brigades by 1942, but by the end of 1939 there was only one, with a second in the process of formation and both equipped with obsolete junk. It was very much a case of too little too late and Maczek’s hard won concepts and ideas for mobile armoured warfare had clearly been ignored by the Polish leadership.

A Polish main battle tanks… ummm yeah, ok!

However, Maczek would have his day.

Maczek finished the Polish Bolshevik war as a Captain and two months after the signing of the peace treaties, he was sent to join the 20th Infantry Division as a Staff Officer. From 22nd January 1922 until 1930 he held the rank of Major which was backdated to 1st June 1919. A staff appraisal of Maczek from this period, talks about him in glowing terms saying that he was a conscientious officer with massive ambition and his relationship with his subordinates was model. He was extremely fit and had an ability to quickly orient himself in confused situations. He displayed admirable independence and was self-reliant. In modern terms he would be considered very much a self-starter.

Polish anti Bolshevik propaganda poster

However, no matter how well Maczek’s career was going, by 1921 Poland was already exhibiting worrying signs. Poland’s most obvious problem was being sandwiched between two aggressive neighbours who had, until recently been at war both against each other and in one degree or another, against the Poles themselves. Following the First World War debacle and disasters Germany would inevitably be quiescent for a decade. This meant that the main focus for defence was against current and hostile communist intent. When Hitler took over Germany and began extensive rearmaments, Poland acquired hostile camps on both sides. It should also be pointed out that despite Germany’s crippled position through the twenties, they still remained very hostile towards the Polish state and plotted with the Soviets, even going so far as to resurrect their nascent armoured formations and Luftwaffe with the help of pitching camp in the Soviet Union. This entire situation was exacerbated by the fact that there were more than a few Western statesmen who did not even agree with the reformation of the Polish state.

The signing of the Treaty of Riga 1921

There is also a theory that at the Treaty of Riga in 1921 which settled the Polish Bolshevik War, the Soviet government tricked the Polish government into accepting more territory than it originally intended to take, in the belief that the more non Poles there were living under Polish rule, the more unstable the country would become. In fact, by 1930 Ukrainian hostility towards Polish rule was so enflamed that full on insurgency warfare was being waged, similar to that of the IRA against British rule. The Polish army undertook a pacification operation which was badly mishandled and saw the Polish troops rampage in Galicia.

It would be reasonable to assume that the incredible victories scored against the Soviets would serve to bind the Polish military together into a unity, but in fact the opposite happened. The Polish military descended into schism and factionalisation between the Pilsudski trained Legions and the professional troops from the former Empires. What’s more, the military developments that were available to Poland were hampered and somewhat suppressed by the military ignorance and illiteracy of Pilsudski and his cohorts, despite the Polish Soviet war being the largest conflict of the Interbellum up until 1936 and the Spanish Civil War. Lessons to be drawn were abounding. The mountain of publications disseminated by modern, professional and forward thinking officers such as Maczek went ignored, to their mounting frustration and resulted in Pilsudski, who practically WAS the army, preferring the company of his Legions not only politically but after 1921, also militarily.

Pilsudski and Legion Officers in Kielce

By ignoring the experiences of his professional troops who had fought all around Europe, Pilsudski divorced himself from his closest ally the French, along with their modern (although admittedly short-sighted) doctrine. The conclusion of the Franco-Polish alliance in 1921 led to the French reorganising the Polish army with the alliance stipulating that the Poles introduce 2 year conscription terms and that they maintain an army of 30 divisions modelled on that of the French army.

Typical Belarus grasslands

A word should be said from Marshal Pilsudski’s position however. Part of the problem with the Alliance conditions was the inherent lack of mobility. Whilst this could perhaps be understood and agreed to when fighting Germany, given the experiences of the Western front, positional warfare when fighting the Bolsheviks across the wide open spaces on Poland’s Eastern borders was just not practical. There simply was not enough manpower to cover the space.

A further issue was that the civilian population of Poland was becoming wary of the power that Pilsudski held and to pre-empt this, they actively moderated the position of president when they drew up their constitution in 1921, a position that many assumed Pilsudski would occupy. Flying in the face of public opinion however, Pilsudski refused to take the position of a weakened presidency.

Gabriel Narutowicz

Despite his withdrawal from politics, the Polish military was still the guiding light of the country and it was through Pilsudski and the military that the country’s first president, Gabriel Narutowicz found his way to election. The assassination of Narutowicz in 1922 made Pilsudski furious and he held the government morally responsible. There is a theory that those who were responsible for the assassination were also working towards the death of Pilsudski himself. In 1923, Pilsudski withdrew from public life in disgust.

Between the years of 1918 and late 1923, Pilsudski had simultaneously held the offices of Head of State and Supreme Commander. He did not contest the weakened presidency in 1922, leaving it open for another to step in. As a result of this farce the Sejm (Polish Parliament) had to endure an adjusted relationship with the military. The period between 1921 and 1926 was characterised by the subjection of the military to civilian oversight, conducted partly through the office of the President as laid out in the 1921 Constitution. The President was not accountable to the Sejm, but his responsibilities were carried out by ministers who were. He was the highest ranked military officer although by constitutional decree, in times of war he was not allowed to be the supreme commander and was to work equally alongside the Cabinet, whilst the Minister of Defence would appoint a Commander in Chief. In short, the President was the head of the army, but its parliamentary dealings were all carried out by the Minister for War, an officer who was totally subservient to the Sejm for all military acts, both in wartime and peace. It is this interference in military matters that Pilsudski resented so deeply, which when you think about it is quite ironic. One military amateur resenting the interference of other military amateurs!

Sikorski as President

Between 1921 and 1926 Pilsudski was thwarted in his attempt to become the sole ruling authority in Poland, with successive Polish parliaments removing Pilsudskiites from positions of authority and replacing them with their opponents, both politically and militarily. It was during this period of true democracy that Maczek and his future sponsor, General Wladyslaw Sikorski, would meet. Sikorski’s political career would begin at the same time as he was nominated to be Chief of the General Staff. Sikorski served Pilsudski faithfully in this role, but after the assassination of Narutowicz and then Sikorski’s appointment as Prime Minister, Pilsudski became embittered with the whole political process in Poland.

During 1923, Sikorski was nominated to the post of Inspector-General of Infantry and later also accepted the post of Minister of Military Affairs. It was during this period that the strategy of bringing the Polish civilians under the control of the military began to take shape. Pilsudski was furious and launched an anti-Sikorski propaganda campaign in a bid to gain public support as he sought to remove a political enemy, which is how he now perceived Sikorski. He thought highly of him as a military commander but politically, he felt that he couldn’t trust him as far as he could throw him.

Further exacerbating the political situation in Poland was the Sejm who were repeatedly ignoring the complaints and concerns of the ex-Legionnaires, causing them to nurse grudges against the Polish authorities and professional military officers, especially those of the former Austrian army. This is an important point here because Pilsudski always sided with these Legionnaires and chose them as his reference and support group instead of the army, so he would always be willing to take up their cause as his own.

Pilsudski in Warsaw executing his coup, 1926

Confronted by an ineffective civilian administration, still retaining the loyalty of many professional military officers, buoyed on by a tide of popular support from the Legions, and indeed the wider nation as a whole, Pilsudski launched his coup in May 1926 quickly assuming the reins of power. Indeed, there was widespread relief when he did claim power.

The streets of Warsaw at the time of the May Coup 1926

He justified it as a necessary measure to prevent the collapse of Poland into chaos. This was supported by the fact that the Polish military was the only authority that Polish civilians respected. Despite the fact that he claimed he was concerned about the Polish military becoming a tool for Polish politics, this is exactly what he used it for. Politics! Once he assumed the dictatorship of Poland, military professionals were resigned to taking a back seat and the large number of ex-Austrian military professionals, along with the political enemies of Pilsudski, were purged from positions of any authority. After the coup, many junior officers would come to complain that they had been passed over for promotion for being on the wrong side, or to coin a phrase they were ‘zmajowany’ or ‘May-ed!’

The investing of Belvedere Castle, Warsaw. May 1926

Of more critical importance however were the senior officers, including Sikorski, (a quite capable tactician and strategist in his own right and a modernizer), being placed into professional limbo, being neither purged nor yet involved in military life. Rothschild points out that, Pilsudski owed Sikorski a debt of gratitude for not allowing his Lwow regiments to become involved in the fighting at the time of the May coup in 1926, as Sikorski and his men remained aloof from the revolt. Direct support would have been preferable as it may have lent a veneer of respectability to the coup, and perhaps preserved the interwar Polish army from the amateurs that would eventually lead it to destruction.

Polish Legions on parade

These purges reversed the trend that had favoured career officers and saw the rise of political loyalists, especially those of the wartime legions. Some startling figures show that in 1920 only 10% of the officer corps were ex Legionnaires, whilst by 1939 the Infantry officer hierarchy (both active and reserve) was occupied by 75% of ex Legionnaires. Even the cavalry (including motorised) was 54% ex Legionnaires, as was the Inspector General, the Chief of the General Staff and his deputies and even the Minister and Deputy Minister for War.

A further damaging consequence of Pilsudski’s rule was that by 1939 he was deciding on all appointments personally within the military, usually following Q&A sessions which he would lead at wargames conferences and events. This is just another indication of the amateurish apparatus of the Polish military during this period. By 1939 only 4.84% of the officers in the army were graduates of military staff colleges. Is it any wonder Poland suffered such a dramatic collapse in 1939 on the back of communications breakdown, lack of supply and poor distribution of military assets? Poland’s individual serving troops could have been the best in the world but they still wouldn’t have been able to win a game of draughts when contending with this shambles!

The lack of formal military education within the officer corps between the wars was to prove disastrous in 1939. The politicisation of the officer corps at the expense of professionalism was to lead to a deeply riven factionalised army throughout the Second World War, a period when it would have served the state of Poland far better, by focusing on ways to combat the Nazi and Communist steamrollers that were riding roughshod over their homes and land. All of this however, was an arena that our erstwhile hero Maczek was always proud to remain aloof from.

Portrait of Pilsudski as virtual dictator of Poland

Pilsudski ruled Poland as a dictator from 1926 until his death in 1935, his rule becoming harsher with each passing year and most especially after the 1930 elections, which he and his supporters stole using intimidation and fraud. In 1935, the Pilsudski junta actually threw out the 1921 Constitution. They replaced it with the more autocratically and militarily friendly April 1935 Constitution which was tailor made for Pilsudski, although he died before he was able to enjoy it. That’s karma I guess eh?

The 1935 Constitution was to have serious future consequences for the State of Poland which Pilsudski and his cronies could not have anticipated (or at least, could only have anticipated if there were any serious geniuses at work for Pilsudski). Poland’s Government in Exile, after 1939, claimed its legitimacy from this 1935 Constitutional Document. In 1943, the Soviet government questioned the legitimacy of the Polish Government in Exile and their suitability to rule, claiming that the 1935 Constitution was illegal, thereby destroying the legitimacy of the Government in Exile in one fell swoop. This was a measure that the Western allies were powerless to dispute, as one of the prime conditions of the re-establishment of the Polish state was that it existed as a democracy and NOT a dictatorship, which the Western powers were absolutely opposed to.

The signing of the April 1935 Constitution

Pilsudski’s death was a shock to the Poles and made more grievous by happening at a time when tensions across the entirety of Europe were just ramping up. Within Poland, there was a resultant state of political unrest. There had been little to no consideration to a successor once Pilsudski shuffled loose his mortal coil. They knew of nobody who could replace him.

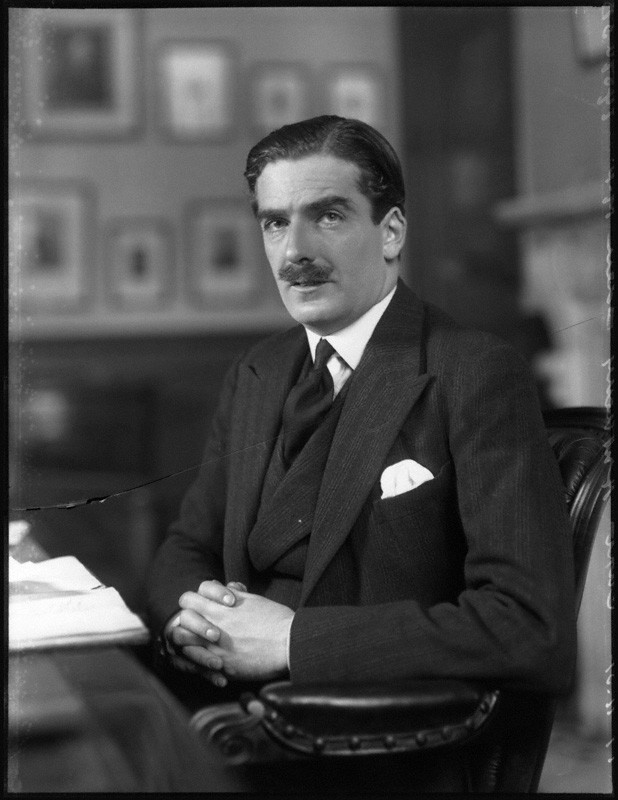

Anthony Eden

Serious consideration should have been given to this in 1931 when Pilsudski suffered a serious bout of illness and realised he was dying. He was in fact falling victim to cancer. The visiting British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden (my God! This guy gets everywhere. This guy is a REAL unsung hero in British history. Did you know he single handedly stopped the 1st Indochina War being turned into a nuclear war by Eisenhower and CF Dulles? What a DUDE!!!), after meeting Pilsudski on 2nd April 1935, reported that he appeared to be senile. As Evan McGilvray states; ‘Despite his being associated with the resurrection of Polish independence and its preservation, he failed to consolidate his rule. Indeed after his death the sham of his regime was exposed’.

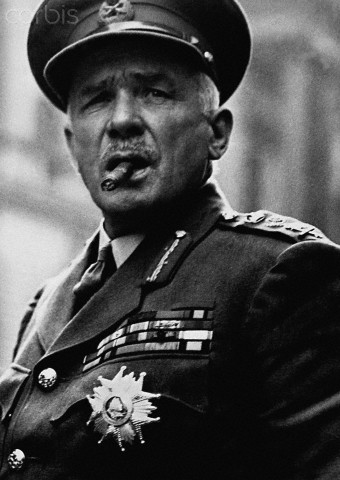

After Pilsudski’s death, the actions of the Polish military under the auspices of Marshal Edward Rydz-Smigly and Colonel Jozef Beck became overtly political. Colonel Jozef Beck, Poland’s Foreign Minister, was already well known as a favourite of Pilsudski, but Rydz-Smigly was an unknown until he was touted as a successor to Pilsudski. Until this time he was considered to be apolitical. It may be assumed that his appointment was, in part, a measure to settle the tensions between the professionals and the Legionnaires in both military and political circles. Rydz-Smigly was born in the Austrian partition of Poland and had joined the Strzeleczy early on. In 1910 he was conscripted into the Austrian army.

Kazimierz Sosnkowski in 1926 at the time of Pilsudski’s coup

He completed Officer training in 1912 leaving the academy with good grades, and despite his professional military background, his support of Pilsudski’s coup ensured that his military career prospered. Many had assumed that General Kazimierz Sosnkowski, who had shared a German prison cell with Pilsudski between 1917 and 1918, would have succeeded Pilsudski but he failed to support the coup leaving him in the doldrums.

As with Pilsudski, Rydz-Smigly was neither Head of State nor Prime Minister but as head of the Polish Army, he expected all to bend to his will. It is at this point that professional British Military opinions start to reveal the depth of decrepitude prevalent in the Polish military apparatus. General Edmund Ironside, who led the British military mission to Warsaw in summer 1939, made a note of the fact that both President and Prime Minister were subservient to the military and most definitely knew their place! “The president is a figurehead…and knows it. The prime minister never appeared. The two men who had all of the power in their hands are the Foreign Minister; Colonel Jozef Beck and the Marshal Rydz-Smigly”

General Kazimierz Sosnkowski in 1943

At this point, it is also worth making an observation. This treatise has spent time criticising the amateur legions when compared with the progressive and professional nature of professional officers, leading to a conclusion that all Legionnaires were bad and all professionals were good. This is of course a heavy generalisation, brought into sharp focus, when one compares the military and political abilities of Rydz-Smigly (a professional) against Sikorski (a Legionnaire). Rydz-Smigly’s incompetent strategy and marginalisation of opponents such as Sikorski (and to some degree Sosnkowski), would prove catastrophic in the first week of the Second World War. Poland, as a shattered nation state can count itself extremely fortunate to have had such capable and dedicated officers such as Sikorski and Sosnkowski, without whom Poland may very well have been consigned to the ashes of history. Sikorski, Sosnkowski and others like them kept the dream of Poland alive for two generations!

Polish troops swearing allegiance to the flag!

Not only was Poland’s political spheres dominated by Pilsudskiites after his death, but also the military and its future development was still held in thrall to the memory of the Marshal. In 1935 Germany was most definitely rearming, whereas the Polish military was still horse reliant and backward looking, with no appreciable changes having been made in the 15 years since the victory at Warsaw. It was only in 1938 that the General Staff ordered exercises, based on the real material capabilities of the forces and not its theoretical status. By this time it should also be noted that poor foreign policy, illegal home rule and poor political and military choices in development, had ideologically positioned Poland very much in line with Nazi Germany which drove the wedge deeper between Poland and its allies.

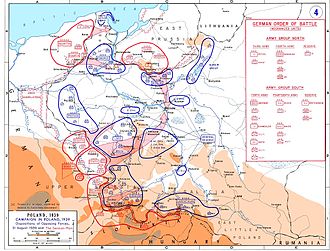

Distribution of Army Groups under Plan Zachod (Plan West)

The main exercises carried out were done so with the idea of resisting the Soviet Union, represented by ‘Plan W’ (Wschod – East) which revealed a lack of ammunition available to the troops. Plan W was finally completed on 20th March 1939 whilst the plan for war against Germany, ‘Plan Z’ (Zachod – West) was not even started until 4th March 1939 once the political relationship with Germany had deteriorated beyond repair. Plan Z was defensive in nature with the time, place and nature of the attack being chosen by the enemy. There is a strong case to be argued that a handing over of initiative to this degree is criminal, especially when a military realises that it is outnumbered and therefore will never be able to force a numerical superiority at the point of conflict so surrendering the benefit of any force multipliers. Why they never took this into consideration, we may never know, but it says an awful lot about the stupidity of the men guiding Poland into its conflagration. By March 1939, Poland was surrounded from 3 sides by Nazi Germany (East Prussia, the German border itself and Slovakia) with the Soviet Union on the fourth.

Karski observes that in 1939, Poland had fewer military strategies designed and implemented than it did in 1925, the year preceding Pilsudski’s coup d’état and despite 50% of Poland’s national budget being spent on the military between 1933 and 1939, it was simply not enough. According to German dates for the same period, they spent 30 times more than Poland on the Wehrmacht alone, not even touching on the nascent Waffen SS, the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. Ironically, during the democratic era of 1921 to 1926 two military plans had been developed and established in case of war with either Germany or the Soviet Union. As Polonsky says ‘ by this time it was all rather too late’.

Polish and German Officers on exercise in Volhynia 1938

Despite establishing a proper arms industry complex after 1936, politically speaking, by this time Poland compounded its neglect of the military by aligning itself too closely with Nazi Germany. They failed to appreciate the true nature of the Nazi ideology and were far too focused on eyes east towards their traditional adversary, the Bolsheviks. This even went as far as positioning their war industries as far away from the Soviet Union as they could get them… on Germany’s doorstep in Silesia. This total focus on the East was one of the many failings of the Pilsudski era, but more critically, it was one that was carried on by his successors.

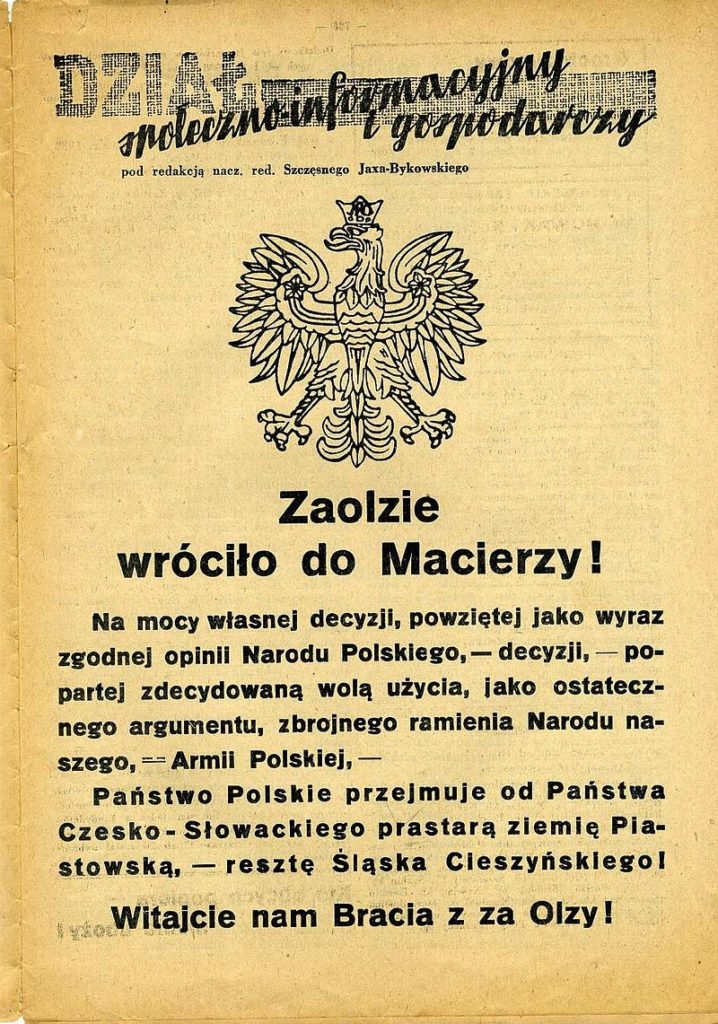

Information Poster about Poland’s occupation of Zaolzie in 1938

Poland’s final act of cooperation with Nazi Germany was the annexation of the disputed territory of Teschen in Czechoslovakia during October 1938, when Nazi Germany dismembered the Czechoslovakian state. To quote Evan McGilvray “This was the nadir of the Polish Military regime and caused Poland to lose support in the West. Indeed, Sir Alexander Cadogan, the Permanent Under Secretary at the Foreign Office referred to Colonel Beck in his diary as a ‘Brute’, in reference to the Polish ultimatum to the Czechoslovak government”.

The Polish annexation of Teschen (otherwise known as the Zaolzie Incident), was the first time since the Polish Bolshevik war that Maczek saw active service outside of Poland’s borders.

Stanislaw and Zofia on their wedding day

Since 1921, Maczek’s career had been quiet, almost quiescent, although his personal life was a little more active. On 22nd June 1928 he married Zofia Kurys, a descendent of a family deeply involved in the 1863 insurrection against Russian domination. They had two children in Poland, Renata who was born in 1929 and Andrzej born in 1934, who would eventually rise to become Dr Andrzej Maczek, a senior academic at the University of Sheffield. This little family were destined to follow Maczek into exile after the collapse of Poland in 1939. A third child, Magdalena was born in exile, sadly handicapped, although the Maczeks, as stoic as ever looked after her diligently and she outlived both her parents.

Colonel Stanislaw Maczek in 1934

His career in interwar Poland was slow but steady. On 22nd January 1922 he was promoted to Major and was involved in General Staff work as well as heading up the Intelligence division of the General Staff. On 30th October 1927 Maczek was promoted once more, this time to Lieutenant Colonel, making commander of 76th Infantry Regiment. This was followed by another command, the 81st King Stefan Bathory Rifles, stationed in Grodno.

As it turns out, the Zaolzie incident was a massive mistake on Poland’s part. During the Second World War it would rebound and hurt the Polish Government in Exile when Winston Churchill recalled it and condemned it. Even the surrendering Slovakian general predicted that very soon Poland would be surrendering her lands to Hitler. This proved to be the case and the whole incident of the occupation of Teschen proved to be an extremely foolish mistake compounded by the involvement of our hero in it.

Polish troops marching across the border of Teschen 1938

Being a professional soldier, Maczek could do nothing other than obey his orders and move into Czechoslovakia. This land grab was a disaster for Poland, even if they were right in claiming that Czechoslovakia had annexed the lands in question in 1919. Whilst Poland was absorbed with events on their eastern borders, the Polish foreign minister, Beck, lacked the wherewithal to realise that executing a land grab alongside Nazi Germany at a time when tensions in Europe were at the highest level since 1914, was a gross political blunder. It positioned the dictatorship of Poland as sycophants of Nazi Germany and wholly lost sympathy for Poland from its Western allies, a situation which continued throughout the war causing a multitude of complications.

Marshal Rydz-Smigly

One can only guess at the regimes decision to land grab during the Czechoslovakian crisis in 1938, but a suspicion suggests that it was done in the name of popularism. The junta became ever more disconnected from the man in the street, whilst the country began to drift politically and economically. It may even have been done as an exercise to boost Rydz-Smigly’s popularity on the home front.

Maczek was made the commander of the Polish 10th Motorised Cavalry Brigade at the end of October 1938 (following the disastrous field trials earlier that year under Colonel Adam Kicinski), arriving in Warsaw from Czestochowa to receive the appointment, after 18 years quiet service in various infantry regiments as well as the Staff college. For the previous four years, he had been 2iC of 7th Infantry Division.

True to form, Maczek began to read the latest military literature covering his new assets at a voracious rate, as well orienting himself with the political situation between various countries in Europe; especially Italy, Germany and the Soviet Union. He recognised the situation was grim and was bound to deteriorate further. Poland had already occupied Teschen in Zaolzie at the beginning of October and the 10BK was to be sent in to strengthen the claim.

The Black Brigade in Zaolzie 1938

It is around about this time that Maczeks affiliation with the Black Brigade begins. At the time of the Zaolzie incident the Black Brigade was under the command of Colonel Trzaska-Durska and the 10BK became a part of Independent Operational Group Silesia for the duration of the operation and was tasked with moving over the border and occupying the important railway junction town of Bohumin. This was achieved with no problem and the brigade remained in this area for six weeks parading themselves around, waving their banners to much applause from the ethnic Poles of the area.

Colonel Trzaska-Durska

At this point in time Colonel Trzaska-Durska was unceremoniously booted out of the brigade for several significant blunders occurring in the recent operation. Maczek was brought in to take over. He was well received as the men of the Brigade were well aware of his combat record. His new posting came with a warning however. The command echelons were so far singularly unimpressed with what a motorised brigade had to offer and the commander of IOG Silesia stated to Maczek that the Brigade “did not perform” during the previous manoeuvres and so if its effectiveness did not improve “the trials will have to be discontinued”

In the middle of October the brigade was moved back to Bielsko from where they would serve as the mobile reserve of IOG Silesia. Training of the troops with their new equipment began again in earnest.

The 121st Light Tank Company as a part of the Black Brigade

At the start of November the Brigade was used to secure further towns and villages in Slovakia which led to arguments with Slovakian army officers and an exchange of fire over the demarcation line between the two states. One of the 24th Uhlan officers became a casualty and the Slovaks withdrew.

On 1st December 1938 the 10th Motorised Cavalry Brigade was removed from Independent Operational Group Silesia and returned to its depots.

The 10th Motorised Cavalry Brigade was the only fully motorised asset in the Polish army, but Maczek’s ‘Flying Column’ and ‘Storm Battalion’ of the 1920’s were suddenly remembered in Warsaw after years of neglect. As war beckoned people started to remember Maczek!

General Sir Edmund Ironside

After March 1939, with Germany’s absorption of the remainder of the Czechoslovakian state, Hitler turned his attention to Poland. Great Britain made promises to stand by Poland in the event of war, a rash act according to General Edmund Ironside, as there was very little that Great Britain could immediately achieve in a ground war as the British strength was in its navy. However, Poland was not alone in being politically outmanoeuvred, as both France and Great Britain were also flanked by the more aggressive German foreign policies of the 30’s. The governments of France and Great Britain were simply not prepared for the depths of deception practised by Hitler, who was quite clear and outspoken in his intentions for Eastern Europe.

Western European statesmen were still blindly ignoring Hitler’s rhetoric, continuing in their French speaking, political twilight of Gentlemen’s diplomacy. Finally however, Hitler let slip the dogs of war and the face of Europe was changed forever…